Just to keep life simple, let's put Sensor 1 at North and Sensor 2 at East.

Just to keep life simple, let's put Sensor 1 at North and Sensor 2 at East.(This is the continuation of an article about the use and abuse of brainteasers in job interviews. This is the final page, and contains solutions to problems discussed earlier in the article.)

The first move is clear. The only possibility is to take the chicken across, since the only things you can leave together unattended are the fox and the grain. From there on, there are two symmetric solutions: (1) go back empty, ferry the fox across, go back with the chicken (leaving the fox alone on the far shore), drop off the chicken on the original shore and ferry the grain across, then go back empty and finally ferry the chicken across or (2) go back empty, ferry the grain across, go back with the chicken (leaving the grain alone on the far shore), drop off the chicken on the original shore and ferry the fox across, then go back empty and finally ferry the chicken across.

There are an infinite number of such places, all near the South Pole.

Basically, the key is to find a place where you can walk one mile east and

be back where you started (since, in that case, the inital one mile south

and the final one mile north will simply cancel each other). The most

obvious such place is to be just far enough from the south pole that

walking one mile east means walking one circuit of the (unique) latitude line that is exactly one mile long. That latitude line is approximately 1/(2*pi) miles from the pole, so you would start by heading south from approximately 1+ 1/(2*pi) miles from the pole. I say approximately

because, once again, the curvature of the earth enters the picture (although no more so than in the assumption that in the US or Western Europe a north/south line and an east/west line make a right angle).

Any point 1+ 1/(2*pi) miles from the pole will do for a starting point, but this is not the only valid distance from the pole for a starting point, just the northernmost. A bit closer to the pole, you have a place where walking one mile east will make two circuits of a latitude line, then another where it will make three circuits, etc. The sequence is infinite.

Ideally, you place the sensors ninety degrees apart on the wheel. The intuitive way to think about this is that, just as placing the sensors on the same diameter means that the two sensors give no more information than one, you get more and more information the farther apart you move the sensors. At ninety degrees, the information is maximized. You will have the shortest (average) time until you know which way the wheel is spinning.

Just to keep life simple, let's put Sensor 1 at North and Sensor 2 at East.

Just to keep life simple, let's put Sensor 1 at North and Sensor 2 at East.

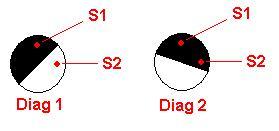

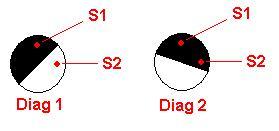

Given that the sensors are appropriately placed, you have to keep sampling until the system transitions either from a state where both sensors see the same color to a state where they see different colors or vice versa. For example, given the positions we've selected, if you start with Sensor 1 seeing black and Sensor 2 seeing white (Diagram 1), then later Sensor 1 continues seeing black and Sensor 2 also sees black (Diagram 2), the wheel must be spinning clockwise. Conversely, the opposite pair of observations would mean the wheel is rotating in the opposite direction. More precisely:

| Earlier observation | Later observation | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|

| North = Black East = White |

North = Black East = Black |

Clockwise (the case illustrated above) |

| North = Black East = Black |

North = Black East = White |

Counterclockwise |

| North = White East = Black |

North = White East = White |

Clockwise |

| North = White East = White |

North = White East = Black |

Counterclockwise |

How long does it take to know which way the wheel is turning? Ignoring sampling rate, in the worst case, we need a quarter-turn of the wheel (there are four equally spaced transitions per revolution of the wheel, and we need only one). Given the issue of sampling rate, we need a tiny bit more than that, since we need to get one sample after the transition.

I already mentioned that in the need-a-key-to-lock-the-box scenario, and without king-to-king communication, the pirate can take the box with the diamond locked in it, pretend to deliver it but actually hold onto it; then when the Daughter King gives him the key, he can sail away with the diamond and the key. However, in this scenario, the pirate will probably never get to do business with these kings again. Instead, a clever pirate exploiting this opportunity might actually:

The above scenario relies on lack of communication and lack of the ability to lock the box without using the key, both of which were asserted by the interviewer. However, as I said, I believe the problem is flawed even with communication and with the ability to lock the box without using the key: no matter what you do, the pirate at some point has the diamond in his hands, albeit in a locked box. The diamond isn't directly worth anything to him in that state, but it isn't worth anything to either king either. The Daughter King may not yet have handed over the key, but he can't get to the box and the diamond without the pirate's active cooperation.

At this point, the pirate can hold the box and the diamond for a ransom anywhere from zero to the price of the diamond. If I were a pirate, I'd probably settle for about half.

<<< PrevCopyleft: With appropriate notification and appropriate credit, non-commercial reproduction is welcome: contact me if you have any desire to reproduce these materials in whole or in part.

My e-mail address is [email protected]. Normally, I check this at least every 48 hours, more often during the working week.